By October 2021, I had written 15,000 words of my novel and only then realised: this is not the story I want to write. I had forced myself into a corner because I believed the story and how I wrote it had to feel and sound like the magical-realism novels I had read. The characters had to use words and behave in ways only characters in a speculative world would.

I was wrong.

In today’s letter, I share how I removed myself from the box of a genre (i.e. resisting its rules) in rewriting the early stages of my work-in-progress.

Overused words make noise.

‘The weapons an author has at her disposal are flawed. Some words feel shapeless and overused. Love, for example. I could write the word love a thousand times, and it would mean a thousand different things to different readers.’

Nothing gives me the eek than reading first and second drafts and finding that I’ve overused certain words. It’s a problem all the best writers have (and solve). How do I go three sentences, an entire paragraph or page, without re-using ‘actually,’ ‘feel like’ and ‘definitely’?

If this isn’t something you’ve experienced in your work, you should pay more attention. When reading your prose, does something sound wrong? Does it feel like there’s too much of something? Does the page feel busy and cluttered? Chances are you’re rereading the exact words over again—crutch words.

They cripple your writing experience.

They cripple your readers’ experience of your work.

If you want your writing to flow smoothly — the words cascading into each other like the ocean — you should check for words you consistently rely on and kill them (the same way you kill adjectives, adverbs and other darlings.) You should also check for clichés and terms always used in the type of prose you’re writing. For example, you’ll almost always see ‘pivot’ in technical articles. In academic writing, it’s ‘however’ and ‘according to’. In business writing, it’s ‘insights,’ and in thrillers, it’s ‘suddenly’ (all otherwise known as buzzwords.)

Finding and replacing these words might require a combination of reading your work aloud, rereading to identify (circle) repeated words, consulting a thesaurus and more. That is, pay more attention. Other times, it might require rewriting to make the work more accessible (i.e. simplify the work.)

Similar ideas, motifs and formats make your work tasteless.

Form: Or format. We’re always so eager to fit the writing we do into a box. Ask: what is the utility of this pattern? And what should I be doing differently to stand out? Here’s a quote I stumbled on recently that is changing the way I write my novel’s first draft:

‘forget everything you think about how words should be organized in a novel. imagine you're writing the first novel the world has ever written then write it. why would you use chapters? why would you use quotation marks to attribute words to specific characters?’

I recently read Girl, Woman, Other by Bernadine Evaristo, a book written without punctuation. In my first attempt to read it in 2020, I stumbled and fell over the first chapter. Armed with audio this January, I reread the first chapter and found myself completely lost in the book. It became even more enjoyable as I saw the apparent need to resist the novel form: the plot and characters fight the absence of ‘other’ in literature. I see no better way to execute a novel with this intention than resisting at all levels.

Sally Rooney, another fave, never uses quotation marks in her work. Her reason is simple: she doesn’t see the need for them and doesn’t understand the function they perform in a novel.

Character and plot tropes: Every genre has a tired trope. Strangers bump into each other and fall in love. Damsels in distress. The dumb blonde. We see them over and over again in romcoms and superhero movies. There’s benefit in leaning into them — they’re predictable: what everyone wants. But you might win more in your writing (gain more attention) when you subvert tropes.

Ideas: In content marketing, you’ll see similar content, concepts and formats. You can copy these, claiming all the best ideas have been taken, and say that you’re bringing something new to the table despite the similarities, but this can be lazy (especially if what you bring is only a slight variation.) While no idea is new on under the sun, multiple things can help you stand out, one of which is proactively thinking of how you can go completely against all existing content offerings for your audience and give them something that’ll wow them. Resistance allows you experiment.

Read books different from the kind of work you’re producing.

I’m forever going to preach that reading great fiction helps you become a great writer — whether you’re a technical or business writer. Similarly, reading and studying poetry helps fiction writers write better fiction. These forms provide a better understanding of the principles behind language, word use, syntax and more that can be replicated in any writing.

Taking it ahead, when consuming content to borrow inspiration, consider reading a book (watching a movie, listening to a podcast, etc.) radically different from your project. For example, if I’m working on a pitch for a documentary series, I’d likely binge-watch Explained since it’s also a documentary series. But because inspiration is not replicating an idea, it might be a better use my time to find inspiration in other forms and content types that can get my creative juices flowing (or you can do both 😅). Watching Friends might give me the inspiration to pitch a three minute show where uni roomates based in Lagos navigate the joys and grief of becoming adults. And this might be the content marketing effort for my fintech creating a savings product targeted at university students. (Not remotely a great idea 👀)

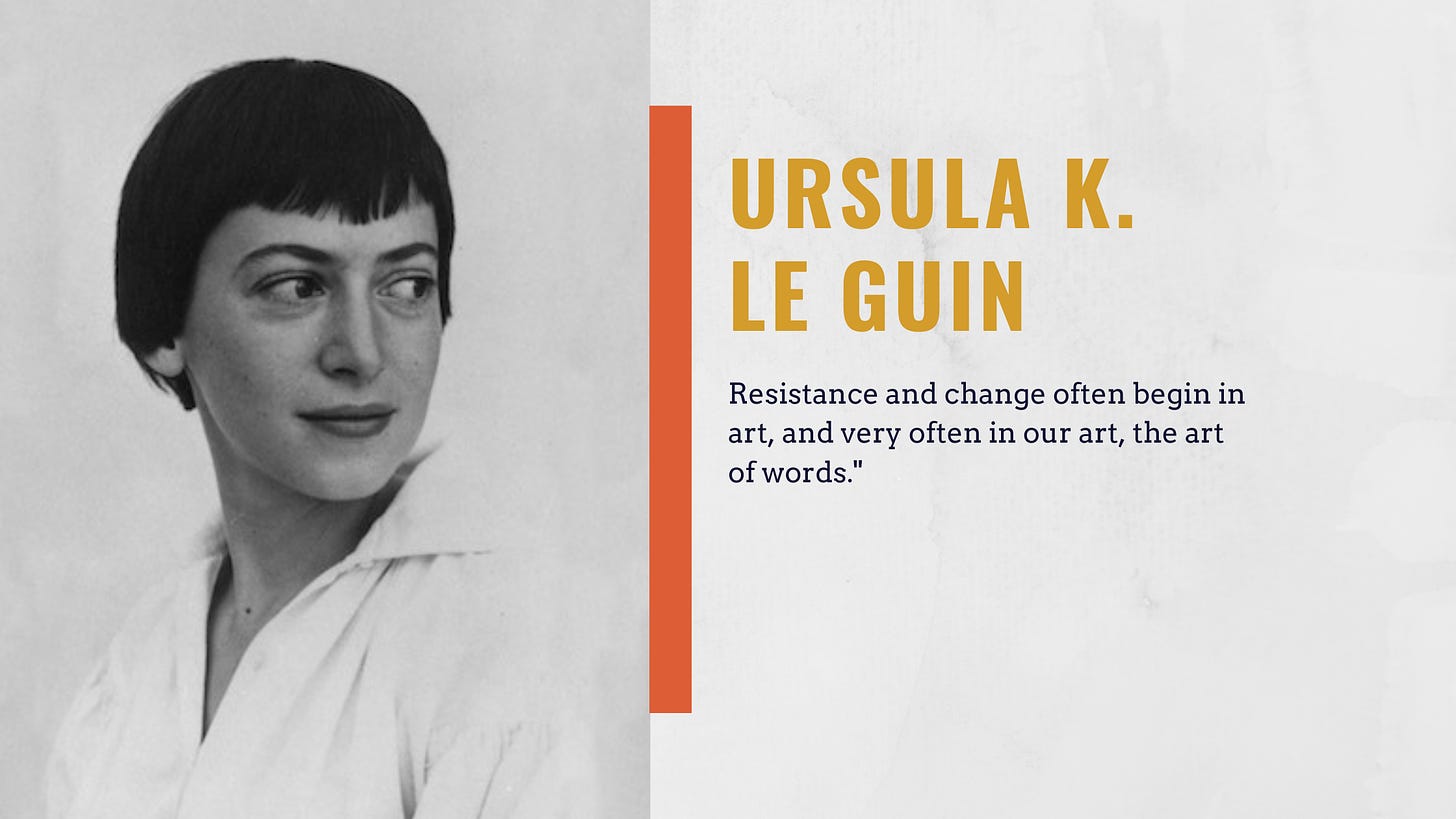

Writing — outside and inside of literature — is critical to succeed in this fast-paced world. The famous advice is that to write well, you must first know the rules of writing and then break them, which is resistance. Resist, resist, resist. The best writers are constantly resisting something, and you’ll find a lot of this in the quirks they employ to write. There’s a well-known rumour that Edith Sitwell, the British poet, lay in an open coffin before writing. In A Natural History of the Sense, Diane Ackerman questioned this. She wrote: ‘What was it exactly about that dim, contained solitude that spurred her creativity? Was it the idea of the coffin or the feel, smell, foul air of it that made creativity possible?’

Resistance.

Kind request: If you read last week’s newsletter and enjoyed the short story I included, I encourage you to share it with your friends and family (I forgot to include a share a button and have now done so at the beginning of the letter). I appreciate your kindness 🌸

Have a great weekend. ❤️

Many thanks to Grammarly for proofreading and Blessing for researching.

This is so true. For example, reading Jose Saramago’s Death With Interruptions subverted my idea of what is acceptable in writing. Since then, I’ve stuck to the belief that I’m allowed to write however I want, contort convention however I want, as long as it makes my writing better and improves how my readers experience my ideas.

Good